Writing an 8086 assembly decoder - Part I

introduction

As part of the work for the Performance Aware Programming course, we are asked to implement a simple program to decode binaries generated for the old 8086 and 8088 intel processors.

This has been one of the most interesting things I’ve ever done.

First thing we needed to decode a simple register to register mov instruction. There is ample material on the web. For one, the course itself give a little explanation, but it frankly quite easier to just look at the processor’s reference manual

I decided to do this in Elixir because, well, I like Elixir.

The course also has a repo with all the exercises. In our case, the asm files and corresponding binaries to know if our implementation works.

Here I’ll just explain how I did things for this first type of mov instruction, because the other ones kind of follow the same process, although the logic for determining which mov instruction you’re dealing with changes quite a lot.

but how does it know what to do?

If you read the manual, you learn that there are 28 possible types of mov instructions that you can give to an 8086 processor.

Which instruction is effectively run depend on the combination of bits you feed to the CPU.

Now, our objective here is to do things backward: given a sequence of bits, what instructions that sequence translates to?

So we’re seeing things from the point of view of the CPU and we want to give our caller a human readable form of the instructions.

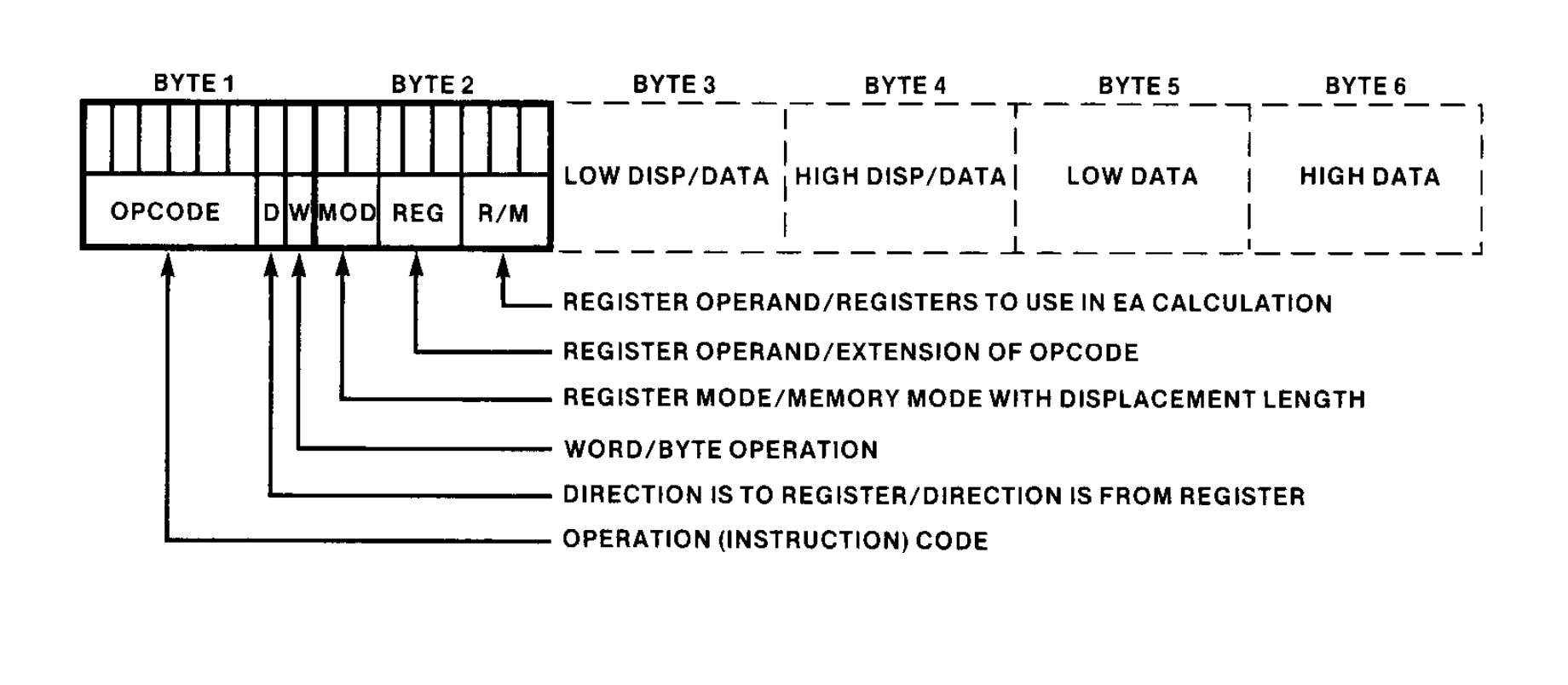

First thing to know is that, given a binary file, the first 2 bytes encode the very first instruction in that file, generally speaking. There are 1 byte instructions, but they don’t concern us at the moment.

So the information that defines what instruction we’re dealing with is located in the first 2 bytes. Here we have something that is very important to note: In order to pack the maximum amount of instruction into memory it’s not necessarily true that the first 2 bytes only encode instruction data. By instruction data I mean the bits that tell us what type of instruction we have, aside from the actual data bits that we want to operate on.

Let’s look at how these instructions are structured:

In BYTE 1 we have:

- The first 6 bits are the opcode, which identifies the basic instruction type (ADD, MOV, etc)

- The 7th bit is the D field, which identifies the destination operand. If 0, the REG field in the second byte are the source operand, if 1, they identify the destination operand.

- The 8th bit is the W field, which distinguishes byte and word operations. This is important because, combined with the REG field, this tells us the name of the register that REG encodes.

In BYTE 2 we have:

- The MOD field for the first 2 bits. Indicates wether one of the operands in in memory or if both are registers.

- Another 3 bits for the REG field. Identifies the register that will be one of the operands.

- And the last 3 bits are the R/M field. This one depends on the value of MOD. It can encode either the register for the second operand or how to calculate the effective address of the memory operand.

It sounds complex. And it is.

In practice, the preceding implies we have to parse each part of the instruction and from there determine what we need to read next, read it and then decide what to read after that, and so on.

Thankfully, Elixir’s function pattern matching feature is very handy for these kinds of situations, since I can just not do if statements. We’ll see further that, despite the flexibility this allows, the code will get quite convoluted with just a few types of movs.

register to register movs

The first thing we’ll be decoding are register to register movs.

Still looking at the manual, they also provide a table that sums up each instruction with their opcodes and what is what in each byte.

There are 7 basic mov instructions, each with their opcode. Register to register movs have the 100010 opcode. So that’s the first thing we need to read.

Now, when setting up this project, I started pretty simple. But this article is already long as it is, so I’m just going to show you the basic structure I came up with to parse files that may or may not have multiple instructions:

defmodule Virtual8086 do

def disassemble(binary_stream) do

assembly = ["bits 16\n\n"]

do_disassemble(assembly, binary_stream)

|> Enum.join()

end

def do_disassemble(assembly, <<>>), do: assembly

def do_disassemble(assembly, binary_stream) do

<<instruction::16, rest::binary>> = binary_stream

decode(<<instruction::16>>)

|> append_to_assembly(assembly)

|> do_disassemble(rest)

end

end

Obviously I omitted most of the file. The thing to understand is:

- I decode the instruction

- Append the resulting assembly

- Go back to number 1 until

restis empty. At which point a return the assembly string

And here is where the pattern matching comes in. For register to register movs, I need to pattern match against the 100010 opcode, which is 34 in base ten, so I have:

. def decode(<<34::6, d_field::1, w_field::1, mode::2, register::3, rm::3>>) do

"mov #{operands(d_field, w_field, mode, register, rm)}\n"

end

def operands(0, w_field, mode, register, rm) do

"#{source_operand(w_field, mode, rm)}, #{destination_operand(w_field, register)}"

end

def destination_operand(1, register) do

@word_registers[binary_digits(register)]

end

def source_operand(1, 3, rm) do

@word_registers[binary_digits(rm)]

end

def append_to_assembly(instruction, assembly) do

assembly ++ [instruction]

end

def binary_digits(binary_string) do

binary_string

|> Integer.digits(2)

|> Integer.undigits()

end

And that’s it, actually. To add one more type of mov, like the 8-bit immediate to register mov, I just need to pattern match against the 1011 (11 in decimal) opcode, which now gives me:

. def decode(<<34::6, d_field::1, w_field::1, mode::2, register::3, rm::3>>) do

"mov #{operands(d_field, w_field, mode, register, rm)}\n"

end

def decode(<<11::4, w_field::1, register::3, data::8>>) do

"mov #{operands(w_field, register, data)}\n"

end

def operands(0, w_field, mode, register, rm) do

"#{source_operand(w_field, mode, rm)}, #{destination_operand(w_field, register)}"

end

def destination_operand(1, register) do

@word_registers[binary_digits(register)]

end

def source_operand(1, 3, rm) do

@word_registers[binary_digits(rm)]

end

def append_to_assembly(instruction, assembly) do

assembly ++ [instruction]

end

def binary_digits(binary_string) do

binary_string

|> Integer.digits(2)

|> Integer.undigits()

end

And since, for this move, I just need the W field, the destination register and the data, I just need a corresponding signature for the operands function:

. def decode(<<34::6, d_field::1, w_field::1, mode::2, register::3, rm::3>>) do

"mov #{operands(d_field, w_field, mode, register, rm)}\n"

end

def decode(<<11::4, w_field::1, register::3, data::8>>) do

"mov #{operands(w_field, register, data)}\n"

end

def operands(0, w_field, mode, register, rm) do

"#{source_operand(w_field, mode, rm)}, #{destination_operand(w_field, register)}"

end

def operands(w_field, register, data) do

"#{destination_operand(w_field, register)}, #{data}"

end

def destination_operand(1, register) do

@word_registers[binary_digits(register)]

end

def source_operand(1, 3, rm) do

@word_registers[binary_digits(rm)]

end

def append_to_assembly(instruction, assembly) do

assembly ++ [instruction]

end

def binary_digits(binary_string) do

binary_string

|> Integer.digits(2)

|> Integer.undigits()

end

And since the W field for 8 bit immediate to register movs is 0…

. def decode(<<34::6, d_field::1, w_field::1, mode::2, register::3, rm::3>>) do

"mov #{operands(d_field, w_field, mode, register, rm)}\n"

end

def decode(<<11::4, w_field::1, register::3, data::8>>) do

"mov #{operands(w_field, register, data)}\n"

end

def operands(0, w_field, mode, register, rm) do

"#{source_operand(w_field, mode, rm)}, #{destination_operand(w_field, register)}"

end

def operands(w_field, register, data) do

"#{destination_operand(w_field, register)}, #{data}"

end

def destination_operand(0, register) do

@byte_registers[binary_digits(register)]

end

def destination_operand(1, register) do

@word_registers[binary_digits(register)]

end

def source_operand(1, 3, rm) do

@word_registers[binary_digits(rm)]

end

def append_to_assembly(instruction, assembly) do

assembly ++ [instruction]

end

def binary_digits(binary_string) do

binary_string

|> Integer.digits(2)

|> Integer.undigits()

end

complexity raises it’s ugly head

Now, after implementing decoding for a few types of movs (three), it’s easy to see that things start to get hectic. I love function pattern matching so, by this point, I had some 4 different signatures to any given function in my Virtual8086 module.

It was time to refactor things a bit. But that’s a topic for a future Part 2.

I think the main take away here is how much easier it is to reason about these things with these kinds of features.

You get a nice separation of concerns without having to reason too much about things, you just focus on what you need to do and write different versions of the same function to deal with different data configurations.